During her Fellowship, Dr Barik researched Victorian-era collaborations, encounters and cross-cultural exchanges between the UK and India around mesmerism – the idea that all living things have an invisible natural force that can elicit a physical effect such as healing. Focusing on England and Calcutta, she examined how mesmerism shaped the movement of people and goods, and how these interactions intersected with race, class and gender.

Dr Barik’s Fellowship activities included hosting two workshops, consulting archives across the UK for a book project and helping prepare materials for the Being Human Festival at Watts Gallery.

We asked Shaona about her research and Fellowship experience.

The Victorians were attracted to mesmerism, a form of hypnotism, for various reasons. It promised to offer alternative forms of cure and claimed to have healing potentials. Before the invention of chloroform or proper knowledge about the techniques of its application, mesmerism was often deployed by doctors to perform painless surgeries.

Apart from the health benefits of mesmerism, it was also used by the Victorians during planchette sessions (for automatic writing), séances, etc., apparently to communicate with the dead. The crisis of faith brought forth by the publication of ideas about evolution and the questioning of the principles of dogmatic Christianity could have made them curious about ghosts, life after death and so on.

Calcutta, the city where I hail from, and which was once the capital of British India, bears testimony in terms of the architecture, cultural influences, communities, etc. to the exchanges between Britain and India during the Victorian period. This is the first aspect that attracted me to research India–Britain mobilities during the nineteenth century. The courses on postcolonial studies offered at postgraduate level at Jadavpur University, my alma mater, made me ponder on how such exchanges and encounters between Britain and India could unravel unknown facets of history.

Novels by Amitav Ghosh, like the Sea of Poppies, deserve a special mention since they inspired me to track and trace cultural history relevant to India–Britain exchanges. My PhD on colonial fiction with a special focus on the ghost stories by the British who visited India during the latter half of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century also inspired me to conduct research in this area.

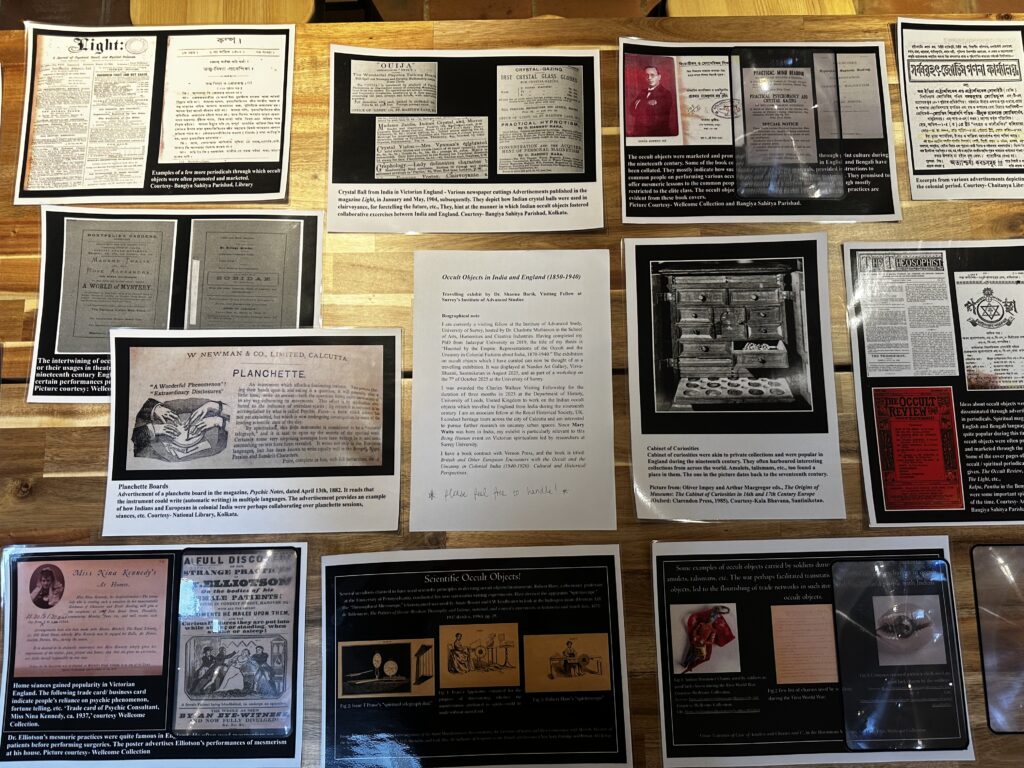

Objects such as the planchette board which could write in multiple Indian languages like Parsi, Nagri and English provide proof of interracial séances (between Indians and the British) which often took place in the households of the elite Indians.

Pictures of the cover pages of books and journals (from spiritualist organisations) in English and Bengali on the subject of mesmerism and advertisements in England of crystal balls from India highlight India–England cultural exchanges and the role of print in such endeavours. Most of the pictures of the objects, trade cards, etc. showcased in the exhibition focused on the idea of India–Britain exchanges over the occult with a particular emphasis on mesmerism.

The occult was often used as an essential tool to voice resilience, question normative ideas and express repressed desires, so the occult will never lose its importance.

Dissatisfaction with socio-political conditions often compel some people to take recourse in the occult, thereby making it a sort of timeless engagement. Recent interest in heritage walks and sites, with a focus on ghosts and spirits across cities in India and London, points to people’s curiosity in such phenomenon.

As an example, James Esdaile, a practitioner of mesmerism at the Calcutta Mesmeric Hospital during 1847–48, mentioned how effortless it was to apply mesmerism on the natives of India because of their submissive and vulnerable nature. This is clearly an indication of how racist stereotypes were often used by some British in colonial India to perform experiments on the bodies of the Indians. The bodies of the colonised people were often the sites of social constructions and contestations.

The study of the memoirs and other documents by the British in India reveal how some of them felt that the Indians were already familiar with mesmerism but perceived it as some kind of superstition. This is an example of how some British often trivialised the cultural practices of the Indians by stigmatising them.

The exhibition I organised at the University of Surrey and then subsequently at the Watts Gallery focused on the pan-continental nature of mesmeric practices in England with special focus on Indian influences. Museum spaces need to be perceived in such light where the dominance of Western knowledge needs to be questioned.

I have signed a book contract with Vernon Press on European encounters with the occult in colonial India. I am planning to apply for the British Academy International Fellowship in collaboration with the University of Surrey. I further intend to organise research exhibitions, a symposium and publish research articles in high-profile journals on Victorian studies.

Travelling exhibit by Dr Shaona Barik displayed at Being Human Festival, Watts Gallery ‘Occult Objects in India and England (1850-1940): Nuanced Perspectives’.

The IAS Fellowship enriched me in several ways. Collaboration with the faculty members at the University of Surrey opened new possibilities and helped me to devise new teaching methods at my institutions. Visits to the archives turned out to be fruitful and will assist in the publication of articles in reputable journals and books.

Back to Q&A features“I was really humbled and glad to have been able to exhibit my work as part of the Being Human Festival in the UK.”